BY HALE BRADT

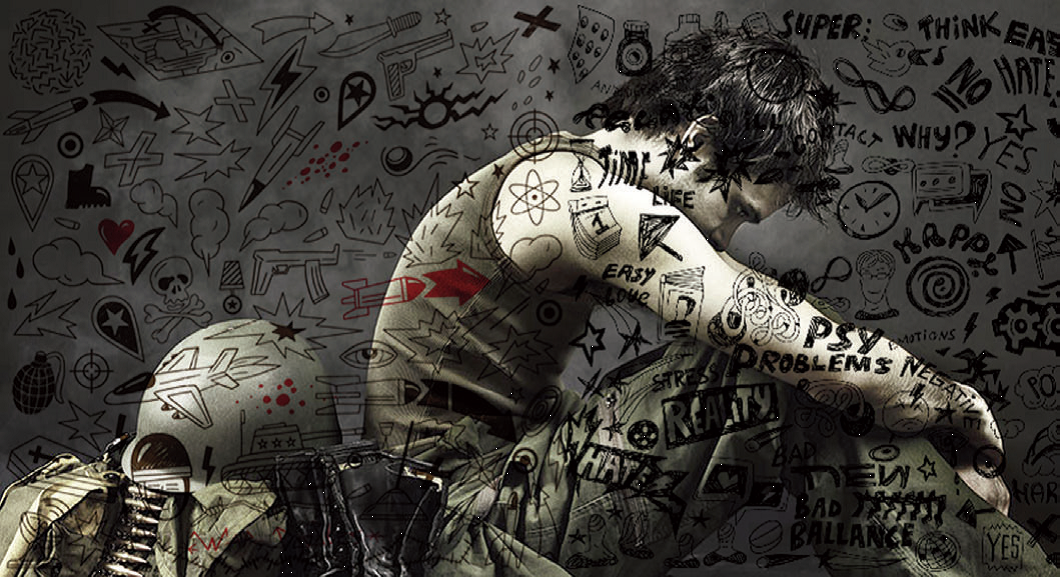

I do not know if my father, Wilber Bradt, suffered from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) when he came home from World War II. I do know that he committed suicide six weeks later. It is known that PTSD sufferers are at relatively high risk for suicide and that sustained combat can lead to PTSD. But there were no overt signs he suffered from “intrusive, recurrent recollections, flashbacks, and nightmares,” as PTSD symptoms are described in a psychiatric reference manual. He may have had them, but he did not speak of such, nor did he mention them in letters he wrote to colleagues and siblings those last weeks. To me, a 14 year old, he seemed quite normal; he communicated freely, and seemed his old self to me.

However, in his writings, he did frankly mention symptoms that to me characterize depression: “The reason I’m still being held here [as an outpatient in a military hospital near our home] is simply combat fatigue. I’m just plain tired, so tired that at first, writing was difficult and enunciation poor and I tended to be hysterical [teary?].” He did not want to return to the high academic position awaiting him at the University of Maine and was “too tired” to seek other employment. “It seems that when I relinquished my command and was told officially I was tired, I just all at once realized and admitted it to myself and then was tired.” The day he died he was suffering from a recurrence of malaria symptoms: chills, fever, and fatigue, which could only have worsened his depression.

Wilber certainly had sufficient reason to be “tired,” or to exhibit symptoms of PTSD invisible to others. Four-and-a-half years earlier, he had entered federal service with his Maine National Guard Unit. After 19 months of states-side training, he spent three full years overseas in the Pacific Theater. He experienced three phases of combat, in the Solomon Islands, New Guinea, and the Philippines. He found himself in life-threatening situations numerous times, was wounded twice in the Solomons, and earned the Silver Star medal for personal heroism, three times in the Philippines.

During most of the combat, he was commander of a battalion of field artillery (500 men and 12 howitzers), but at the end of the war he commanded an entire regimental combat team of 4,500 men that was to be in the first waves ashore on the Japanese homeland had the war continued. On the voyage home, he was senior officer aboard a troopship carrying 5000 men. Upon arrival in California, his unit, the Green Mountain Boys of Vermont, was demobilized. He then commanded… no one. The flight home to Washington, D.C., in the unheated cargo area of a transport plane was not pleasant; when he tried to sleep on the cold metal floor, the engine vibrations aggravated his two-year-old head wound, a small piece of shrapnel lodged in his eyebrow.

MY MOTHER’S STORY IS EQUALLY RICH IN HUMAN DRAMA

When Wilber entered the service, he and my mother agreed that she should invest in herself, in her musical and writing skills as a hedge against his never returning from the war. Accordingly, she took my sister and me to New York City, the cultural capital of America, where she studied piano with an eminent teacher. There, some months after Wilber had gone overseas, she conceived a baby with a somewhat older man, a family friend. As a very religious woman, she must have been in despair at her own actions and the potential consequences, but decided to carry the pregnancy to term, which she did amidst great secrecy and subterfuge. How she dealt with this in the social climate of the 1940s is an intriguing story in itself. All through her pregnancy and nursing days, she continued to support Wilber with encouraging letters and shipped him foods and goods he needed: batteries for his radio, spikes for his shoes, a replacement watch, and more. She did the same for her teenage children and also attended to the needs of her newborn. After the war she supported her family and second husband until the end of her days. She carried on while Wilber was unable to do so. She to my mind is the heroine of the story.

During his long absence, Wilber idolized his wife as a wartime compatriot, mother and lover, without a complete appreciation of her inner needs or the difficulties facing those on the home front. Upon his return home, he probably did become aware of her “transgression” but they may have never talked of it openly during his short visits home. One, of course, wonders to what extent this knowledge affected his decision to end his life. I prefer to think that it was not the prime cause; he had much more to deal with, including the close friends he had left six feet under in Pacific cemeteries, some of whom had been sent by him into the places where they were killed.

Our lives following that fateful day were far from what we had imagined, given Wilber’s survival of all that combat and return home. But our family had endured the shock of losing him when he left for army camps in early 1941. We were able to do so again in after the war. Mother married the father of her wartime baby and joined with him in his journalistic enterprises. My older sister became a journalist of some note, and I became a physics professor. I think the loss of our father gave us a push toward independence that helped us achieve these positions. Or, perhaps, it instilled an insecurity in us that drove us to succeed. But there is no question that we both regretted greatly not being able to share life with him in the succeeding years. It is sad to think that he never knew the fine people we married, nor his grandchildren.

It was 35 years after his death that I came upon a few of the letters he had written to me and was surprised at the high quality of his writing; they were vivid, dramatic, loving, fatherly, detailed, humorous, and insightful. Realizing they were a potential new view into the Pacific War and also to our family’s wartime story, I sought out more of them and eventually retrieved some 700 of them. Indeed they wonderfully portrayed the war and family from a soldier’s perspective. I was energized and wanted to know even more. I studied published histories, searched for documents in government archives, interviewed Wilber’s siblings, military colleagues, and a Japanese colonel who fought opposite him. Many of these individuals were still alive in the early 1980s. I also was able to visit the Pacific battle sites where I found objects he had described—a tank, a coastal gun, and a wooden bridge—and people he had known in the Philippines and in New Zealand.

It was finally, about five years ago, that I decided to pull all this together into a form for the general public. The resulting trilogy, released last year, Wilber’s War, An American Family’s Journey through World War II, tells the story in part through Wilber’s letters and in part with my narrative of the wider context and the family story. My research allowed me to unravel the home-front story, which was at that time was still shrouded in lies and secrecy. That brought about significant reconciliation within the family while my mother was still alive. I believe the story, as it is told in Wilber’s War, honors both of my parents as well as the many other families that undergo long or repeated deployments even today.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Hale Bradt served in the US Navy during the Korean conflict and was a Professor of Physics at MIT for 40 years before retiring in 2001. His trilogy, a boxed hardcover set is available on www.wilberswar.com (use code FFWW for 25% discount). The work is also available as three e-books on Amazon or at www.wilberswar.com. He lives in Salem, Massachusetts, with his wife of 58 years.