ACCEPTANCE OF THE DISABILITY LABEL: IMPLICATIONS FOR THE SOCIAL, EMOTIONAL, AND EDUCATIONAL GROWTH OF THE DEAF CHILD

BY J. FREEMAN KING, ED.D.

Labels are especially damaging to the child who is deaf, and immediately establish low expectations that hamstring the child.

Sadly to say, the perspective expressed by Meniere in 1853 is still a prevalent belief among many educators and medically-aligned professionals in the United States today. A pathological label imposed by society, the medical establishment, and/or educational entities acts as a disabling agent for the success and self-image of the child who is deaf in that it promotes wrong solutions to the educational and social potential of the child.

Labels promote expectations and are insidious. They are especially damaging to the child who is deaf, and immediately establish low expectations that hamstring the child educationally, emotionally, socially, and linguistically. Sensory impairment, hearing impairment, disabled, and handicapped are counter-productive labels, but can become the official identification of the child just as assuredly as a microchip implanted in a new-born.

The old adage, “As a man thinketh, so he is,” is certainly true, yet often those in the hearing majority culture are tempted to proscribe labels and resultant expectations on those in a Deaf minority culture. There exists no higher authority on how a group should be regarded than the members of the group themselves. Regardless of the fact that Deaf people do not view themselves as members of a disability group, the labeling process continues in that there are educators, psychologists, and others who are convinced that the Deaf are disabled and by their refusal to acknowledge it, are simply denying the truth of their disability. By rejecting the disability label, the Deaf are trying instead to promote a new representation of Deaf people.

In all fairness, the Deaf should be viewed as an ethnic group, a socio-cultural entity. An example to justify this distinction is the Deaf preferences in marriage and child bearing. Like the members of many ethnic groups, Deaf people prefer to socialize with and to marry other members of their cultural group. In fact, the Deaf have one of the highest endogamous marriage rates of any ethnic group.

Related to Deaf preferences in childbearing, Deaf parents often express a wish for children like themselves, the same as parents do who do not see themselves as disabled. These views contrast sharply with the child bearing views of disability groups. Members of disability groups desire to have their physical difference valued, as a part of who they are; at the same time, they do not wish to see more children and adults with disabilities in the world.

For Deaf people to acquiesce to how others label them is to misrepresent themselves. Deaf people want Deaf spouses, welcome Deaf children, and prefer to be together with other Deaf people in clubs, in school, at work if possible, in leisure activities, in political action, in sports, and in life in general. The reason for this is obvious—they see being Deaf as inherently good.

The disability label poses an extreme penalty and risk for the Deaf child. The Deaf child who wears the disability label is placed at risk for interventions like cochlear implant surgery that will, theoretically, reduce or eliminate the inherent difference of being deaf. Educators and parents must understand that there are risks and penalties involved with cochlear implantation.

Perhaps the most damaging penalty and major risk associated with cochlear implantation is the advise that parents receive from many special educators, speech pathologists, and medical professionals is in regard to using speech-only and discouraging sign language use. If implanted children are unable to learn spoken English and prevented from mastering American Sign Language, they will remain without a full, complete language for the duration of their lives. Developmental linguistic milestones for signed languages are similar to those for spoken languages; therefore, it is inexcusable to leave a child without fluent language for years on end. It is the overall quality of life, and not just the ear, that must be considered.

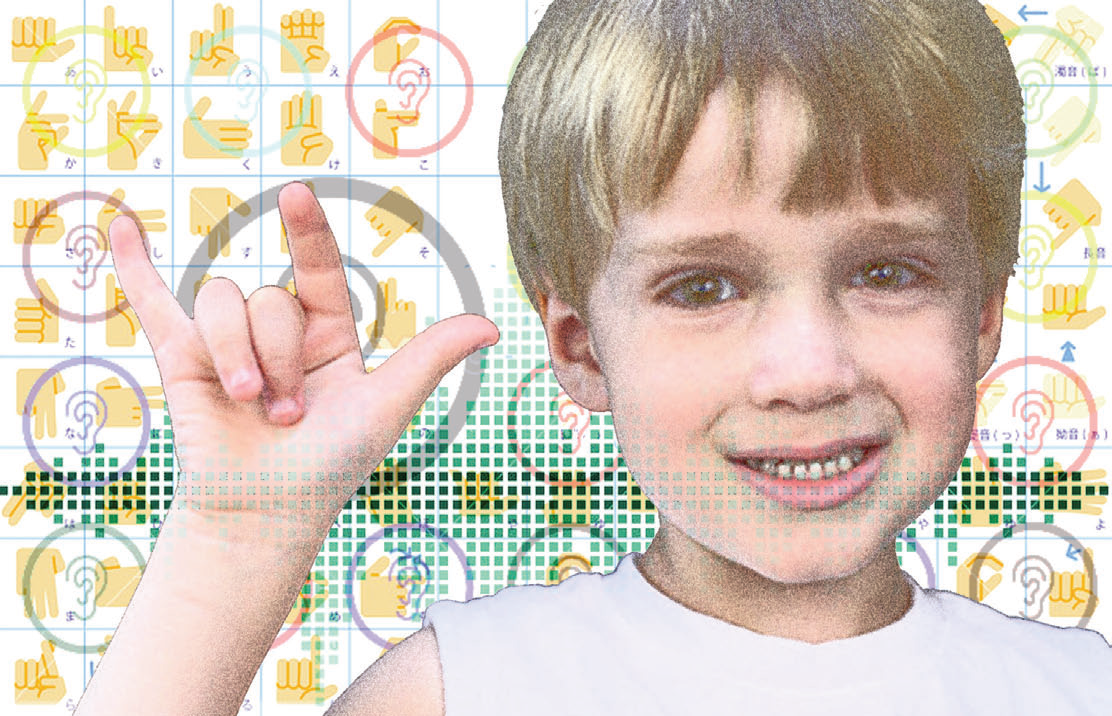

Certainly, all children are born ready to learn language, whether it be American Sign Language, listening/spoken language, or both. The goal of education should be to provide for the basic human right to communicate deeply and meaningfully with others and to develop age-appropriate language skills. Communication involves shared meanings. Without deep and meaningful communication with significant others (parents, teachers, friends, etc.), it is impossible to have shared meanings. Communication of a meaningful nature is a precursor to language development.

It is natural for parents of deaf children to pose the question as to what kind of language will be most accessible for the child: a visual language or an auditory language? The question that can assist parents as they ferret through the biases of professionals regarding methods and educational placement options is whether or not the deaf child is primarily a visual or auditory learner—does the child best access information and language through the visual or the auditory channel? Once this question is answered, the parents can investigate the various methods and educational placement options and choose what best addresses the child’s strength, not his/her weakness—the option that plays to the child’s ability, not his/her perceived disability.

Therefore, how the parents view being deaf is crucial. The parents have two options: 1) they can accept the labels of their child having a pathological condition, of being disabled, of being handicapped, of being abnormal, and the low expectations that accompany these labels, or (2) reject the labels entirely, and recognize that their deaf child can, if given access to language and a quality education will develop educationally, socially, and linguistically on par with their hearing counterparts. The child who is deaf should be afforded the human right of being Deaf, of establishing an identity of which he/she can be proud, of having a fully accessible language that can lead to literacy in the English language, and allowed to dream and realize his/her dreams even as their hearing counterparts are encouraged to do.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

J. Freeman King, Ed.D. teaches at Utah State University.