The “hidden” facet of autism spectrum disorder

BY DR. SHELLEY MARGOW, OTD, OTR/L

Clumsiness is an inevitable part of growing up, and all children bump into objects, drop things and sometimes fall in their journey to adolescence and adulthood. But there are some kids whose struggle to fully participate and learn new skills in daily activities at home, in the playground, and in the classroom is ceaseless. The cause is Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD), a neurodevelopmental condition that affects 5 to 6% of school-aged children according to the National Institutes of Health. It’s often under-or misdiagnosed, particularly in the U.S., where research and attention to the disorder lag those of European educators and clinicians.

As an Occupational Therapists (OT) I know the frustration and heartache of Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD), Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), and associated conditions cause for children and their families. I want to make parents aware of this sometimes ‘hidden’ disorder, including ways to spot symptoms, and clinical methods to diagnose the condition. Once the diagnosis is correct, kids can have the intervention they need to fulfill their potential in school and life.

The ungainliness of DCD-affected children—more of them are boys than girls—may cause people to think they’re incapable or unintelligent because they can’t manage basic tasks. This isn’t true. What is true is that children with DCD usually have average or above average intellectual abilities. At the same time, they have motor difficulties caused by atypical brain development. The formation of new connections between different parts of the brain when learning a skill is affected, as well as impeding the child’s ability to use the information to plan, adapt and control movement.

These kids are often disdained as “troublemakers” or lazy, and teachers may feel the child isn’t trying to meet their potential in the classroom. Parents can become frustrated when they don’t respond quickly or follow instructions. In fact, these children are often trying very hard, but it takes them longer to process and complete activities. Typically disorganized, these kids may struggle with emotions and get easily upset or frustrated, which leads to disruptive behavior.

These children want to fit in, and yet are keenly aware of their differences. A report from the National Institutes of Health has found, “Children and adolescents with coordination difficulties appreciate receiving appropriate treatment, and searching for help can be extremely frustrating for families.” But before you can treat, you need to diagnose.

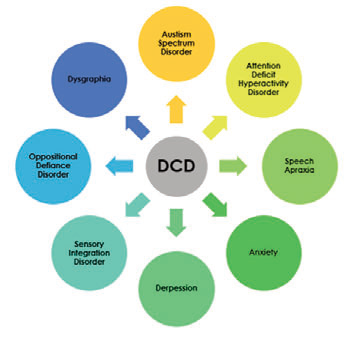

DCD Linked to ASD and Other Disorders. While some people may have DCD in isolation, it’s common that the disorder is just one of a complex of overlapping neurological and other challenges individuals face. Either separately or in amalgamated instances, the conditions can lead to anxiety and depression. In 2017, research from the University of Texas Arlington found that “children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder should be checked for developmental coordination disorder since the two maladies are linked.”

Researchers noted that many individuals with ASD aren’t assessed for DCD although they should be, since motor skill challenges should be addressed early to head difficulties posed to learning and socialization.

The importance of early, accurate diagnosis

Although they are bright, many children falter because their problems with pencil or computer keys hold them back from showing their full potential. Often they’re ‘mislabeled’ or misdiagnosed as slow learners, dyslexic, or having attention deficit disorder, because symptoms may look similar to other conditions. Given extra time to practice lessons and activities, they can participate as part of a team or group. The earlier diagnoses and appropriate, evidence-based therapies begin, the sooner children who are struggling—and developing a negative attitude to school, learning, and social engagement—can be helped.

Symptoms. The hurdles children with DCD face fall into multiple areas and affect everything from simple movement to emotions. Watch for signs in areas like these:

• Communication: Children with DCD may have trouble expressing their ideas or pronouncing words. They may also have trouble adjusting voice, volume and pitch.

• Academics: The inability to write quickly can create classroom challenges, like taking notes and finishing tests. Children with speech difficulties also may have difficulty with reading and spelling.

• Movement: Bumping into or knocking things over may happen frequently. The difficulty with gross motor skills like running, climbing and hoping and fine motor skills like coloring, or playing with Lego make school and social activities uncomfortable.

• Daily Tasks: Mastering independent, everyday tasks can be difficult. At elementary school age, kids may still need help to brush teeth or button a shirt.

• Emotions and Behavior: Children may behave immaturely, be overwhelmed in group settings, find socializing anxiety producing, and difficulty forming friendships. As a result of all these challenges, children may suffer from low self-esteem over time.

• Coping Strategies Can Mask Symptoms: DCD has been called the ‘invisible disability’ because many affected children develop coping strategies, so they’ll fit in better with peers or please teachers. There are things to be aware of that may hint at DCD. For example, they may use computers to avoid handwriting tasks and wear shirts without buttons, or shoes without laces, and avoid gym class or other physical activities.

Diagnosis and Referral Often Begin in the Classroom. Teachers are often the first referral source when they notice poor skill development that interferes with overall academic performance. Many children act out or melt down from frustration. If teachers are aware this is a common behavior in students with DCD, they can take action. Speech difficulty with controlling lips, tongue and jaw movement and coordination, breathing and salivation are easily spotted symptoms and may be the point where referrals to speech therapists begin.

Clinical Assessment Tests of Motor Coordination. There are standard motor coordination tests to pinpoint diagnosis: Bruininks–Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency (BOTMP);10 the Movement Assessment Battery for Children (MABC); the Peabody Developmental Motor Scales (PDMS), and the Test of Gross Motor Development (TGMD).

Quantitative Electroencephalogram (QEEG) for Precise Diagnosis. While more research is underway, a 2016 study verified specific areas of the brain linked to DCD. Neuroimaging isn’t difficult for most children to undergo and is a way to both identify specific conditions and track progress. A quantitative electroencephalogram (QEEG) reveals electrical patterns at the surface of the scalp which reflects cortical activity. The digital data is statistically analyzed and visualized as ‘brain maps.’ In my practice, I use QEEG to record baseline values and check at intervals to track and verify therapeutic progress.

DCD: part of a constellation of related conditions

CORRELATIVE RELATIONSHIPS: As many as half the children with

DCD also have ASD. Many have other developmental disorders.

Neuroplasticity and the Brain. Neuroplasticity, or brain reorganization, is the brain’s ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections. The nerve cells compensate for injury and disease and adjust their activities in response to new situations or changes in their environment, including different types of stimulation and practices. Seeing these adaptive responses and the ability of children to learn new skills with the proper intervention and support is what makes my work so rewarding. Change can happen, and there are even more exciting possibilities that are already here or on the horizon.

New Approaches and Assistive Interventions. Taking a multidisciplinary approach to deliver services in occupational, speech, and physical therapy, and utilizing sensory integration and neurodevelopmental tools specific to each individual and family is the key to a better future for children with neurological challenges. In my practice, I use intensive, neurological treatment to facilitate brain plasticity, including the use of The Margow Model and a next-generation teaching robot, Milo. Milo’s advanced capabilities are purpose-built for autism intervention, special education, STEM instruction and university research. Comprehensive approaches support children to make great strides and better connections to learning, mobility, and improved social interactions.•

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Dr. Shelley Margow is CEO and clinical director of Children’s Therapy Works, a pediatric private practice in Roswell, Georgia and is a consultant to Robots4Autism. After earning her Bachelor of Science degree in Occupational Therapy at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, she received her Post-Professional Master’s Degree from Sargent College at Boston University and also completed Sargent College’s doctoral program for occupational therapy. Dr. Margow published her first book, Is This My Child? Sensory Integration Simplified, in 2014