By Craig Morgan Teicher

Essay

I love reading aloud to Cal. He’s 11, and it’s one of the warmest ways we have of spending intimate time together. We’ve been through all seven Harry Potter books, Roald Dahl’s “The Witches” and “Danny, the Champion of the World,” lots of Sherlock Holmes, several Narnia books and “The Hobbit.” Now we’re in the middle of the last book of the “Percy Jackson and the Olympians” series. Sometimes I think I’m enjoying all of them more than he is — they’re a welcome break from my grown-up literary reading. These middle-grade books are all about story, about characters one instantly loves and the phenomenal trials they endure and are changed by. It’s literature, but without the lengthy descriptions and pretensions to importance.

Cal has cerebral palsy. Wordless but verbal, a prolific utterer of expressive sounds — soft ahhs and mmmms and buhs for happy feelings, and tooth-cracking, high-pitched screams for all manner of discontentment — Cal is a good person with whom to share privacy; he is a gentle and responsive companion for an only child like me, whose energy is drained after too much conversation and recharged by solitude. Cal seems to sense my rhythms and to accompany them. We can pass happy hours alone together in the living room, Cal sprawled on the floor, kicking his way through circles on the rug while I sit in a chair, sometimes on my iPad, narrating my experience of the internet, sometimes reading to him from one of our books.

I also have a 7-year-old, typically developing daughter, Simone, with whom I read a lot. She learned to read herself last year and has plenty of questions and observations about books — whether it’s “Good Night Stories for Rebel Girls,” “I Dissent: Ruth Bader Ginsburg Makes Her Mark” or “Who Was Frida Kahlo?”

I’m a poet; when poets give readings — we are comedians without the jokes — we crave, instead of laughter, a response we call “the poetry moo,” a guttural throat sound that means a line has hit its mark. Of course, our audience is usually imaginary, encountered on the other side of a piece of paper. We envision that moo sounding in some distant room, in a distant time, and are satisfied.

Reading to Cal yields some combination of that imaginary moo — a vicarious confirmation of being heard and understood — and the more conventional verbal affirmation I get from reading with Simone.

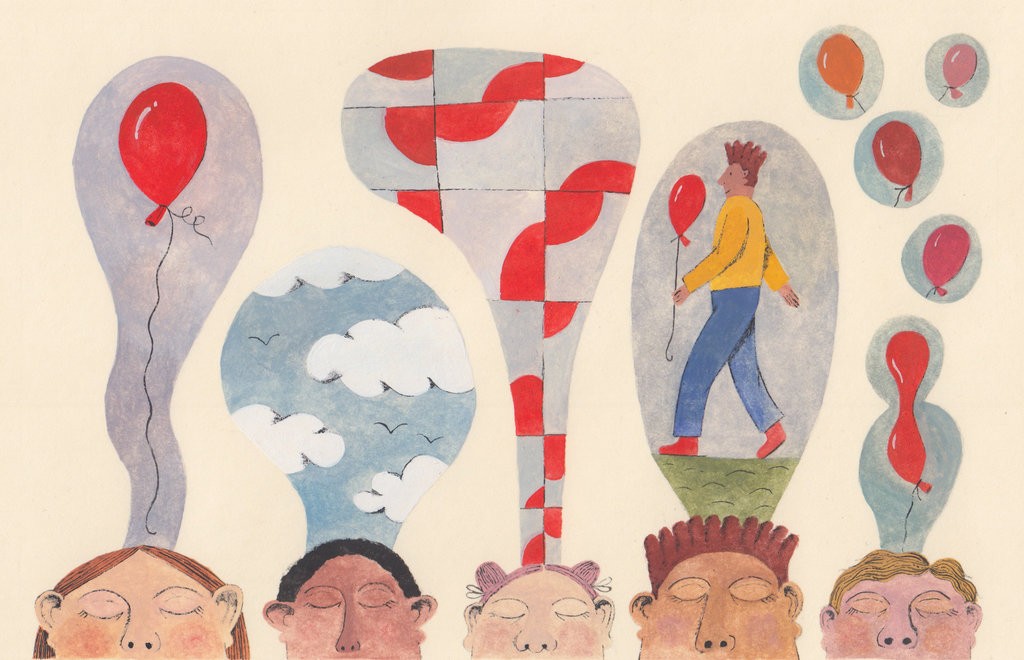

But reading aloud in this way, to and with my children, still feels like a new experience. I had to train myself — it took a couple of years, honestly — to be able to say the words on the page and to also take them in, to understand them, as I would if I were reading alone, to myself, in my head. It’s a many-layered pleasure, chiefly because, unlike with movies, one can supply one’s own images, one’s own sensory details. And I’ve learned some strange things about myself from paying attention to how I do this. For instance, I do not imagine fictional characters as having facial features — in my mind, though I can smell characters and touch the fabric of their clothes, their faces are blank, gray patches. I often wonder why this is and what it says about me.

As a parent of a child with special needs — who is, in special-needs parlance, “very involved,” meaning deeply affected, extremely different from me — a central question of my life is what he is understanding, how differently he apprehends the world. When he hears words, what do they mean? All the context for language that my life — that a typical life — has provided doesn’t apply to him. When he hears the word “red” — he also has cortical vision impairment, meaning that his eyes work perfectly, but they’re like windows his brain isn’t always looking out of — he can’t possibly envision what I do.

We’ve come to the part of “The Last Olympian” (Percy Jackson, Book 5) where Percy and his fellow campers — all young teenagers — are waging war against the Titans of Greek myth, defending New York City, which, in the book, is the present site of Mount Olympus (confusing, I know, but you’ll understand when you read it). A typical 11-year-old might find the budding sexual tension between Percy and his closest friend, Annabeth, boring, the bloody battles awesome and the whole story of heroism and sacrifice a beguiling template for the possible future.

I have no idea what Cal thinks — does he recall, did he understand, the grounding in the Greek myths from the earlier books and our forays into the D’Aulaires’ classic “Book of Greek Myths”? What image does he conjure of Percy? Does Percy have a face? What do faces look like to Cal? Can his mind and body fathom running? I can’t know. What I hope is that my voice, at least — its steadiness, its continuous, faithful tracing of the words — conjures something meaningful.

It’s easy for me to believe that it does. In all the books I cherish, it’s finally the words, how they keep coming in an insistent stream, that I love, even more than what they mean.

Cal seems to listen to me read with deep attention, in a way that is perhaps closer to the way one listens to music, which cleaves closer than words to the emotions it represents, but is impossible to paraphrase. His way of listening seems to me to fulfill our part of the contract books make with readers: that they are here for us, ready to fill the silence, to respond to our longing with steadfast language.

I can only imagine what Cal sees in his mind when I read. Perhaps he simply enjoys the sound of my voice, the pure evidence of my company. And maybe he’s right there with me and Percy and Annabeth on the battlefield. I have no way of knowing. But maybe that’s not so atypical. Neither do I know for sure whether, when I say the word “red,” that any other person imagines the same color I do; as readers and listeners, we fill the pages of books with our own memories and associations, and the characters have the faces of people we recognize, or they have no faces at all. No two people ever read exactly the same book, and that’s as it should be.

Craig Morgan Teicher is the author of several books of poetry, most recently “The Trembling Answers,” and a forthcoming essay collection, “We Begin in Gladness: How Poets Progress.”

Photo: Audrey Helen Weber

View original article here.

Follow New York Times Books on Facebook and Twitter (@nytimesbooks), and sign up for our newsletter.