BY LYDIE RASCHKA

With a grant from the National Inclusion Project, the Marquis Studios Inclusion Program was launched in 2011.

As the six year olds filled the sunny art studio, they chanted the teacher’s name, “Hiromi! Hiromi!” With her frizzy pigtails, crinkly-eyed smile, and blocky gray tunic, Hiromi Niizeki looked like a big first-grader herself.

This was Ms. Niizeki’s second season teaching visual art in the Inclusion Program, a project designed by Marquis Studios. Marquis Studios is a 39-year-old non-profit that provides arts-in-education services to more than 100 New York City public schools. It is the New York Affiliate of VSA, an international organization that promotes arts by, and for, people with disabilities.

Marquis Studios’ founder, David Marquis, has worked in the New York City public schools for nearly 40 years. Sometime ago, he wondered why kids on the autism spectrum were kept separate from the general ed population even when they shared the same building. (The only connection was the @ sign between their names, such as, PS94 @PS281 and PS94 @ PS188.)

In New York City, children who cannot be served in integrated team-taught classes, or in smaller, self-contained rooms are placed in one of the District 75 programs—there are over 80 of these— which are embedded in neighborhood public schools but clustered in their own area of the building. Mr. Marquis noticed something like an invisible crime scene tape barring one population from the other. The teachers and children from the two schools did not know each other’s names, even though they walked down the same halls.

Marquis thought, “Why not bring them together through art?” With a grant from the National Inclusion Project, he did just that, launching the Marquis Studios Inclusion Program in 2011.

ten sessions

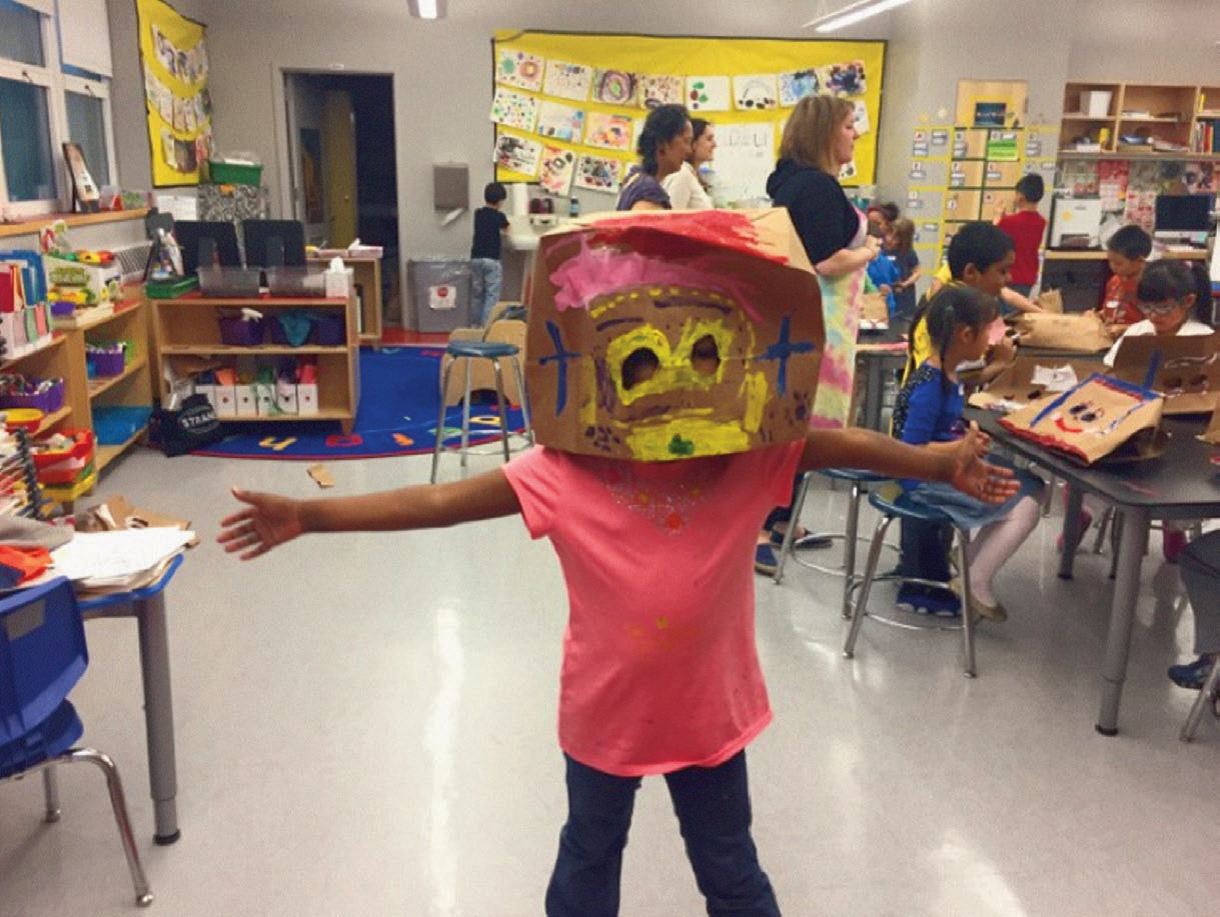

Marquis Studios offers 10 sessions at a reduced price to schools that want to be involved. Last spring, master teaching artist Niizeki worked with a blend of first-grade students from a District 75 school (PS 94)—autism spectrum; and the River School (PS 281)—regular education. Both are located in a modern building on the East River. Her task for all the children was for them to make a mask.

“You will each get your own paper bag,” she said to the more than 30 children gathered on the rug. Inclusion groups are larger because two classrooms are combined. The River School’s art teacher was there to assist, as were classroom teachers and assistants.

Hiromi spoke sparingly, partly because English is her second language, but also because an economy of words is very effective with six year olds.

“You will open your bag and put it over your head,” she said, following her own directions. The kids giggled. She looked comical in her wide-leg pants and black shoes with a bag on her head. Then she removed the bag and turned serious.

“It is not safe,” she said. “What do we need to be safe?”

“Eyeholes!” said the children.

She called on a volunteer and this time when she put the bag on her head she pointed to the general area of her eye Her voice was muffled: “Jamaine, could you mark here for me?” The boy scribbled a circle on the bag.

“We use markers, not pencil,” Hiromi reminded the group, “because pencils can poke through paper.” After her concise demonstration, all the students found their table spots and worked

in pairs to execute her instructions.

routines & collaboration

Routine, Niizeki explained, is the glue that brings the children together and helps them all feel safe. “I struggled the first year,” she confessed. “I tried many things that didn’t work.

As the sessions proceeded over the following weeks, assistant Grace Allen greeted each child at the door with a handshake and a nametag. The children walked directly to their assigned seats and found a stapled booklet filled with blank white paper with their name on it. “The sketchbook system works well because some kids come later than others,” Niizeki said.

Assigned seats purposefully mixed PS 94 and PS 281 children at the same table; it helped them get over their shyness. “The end product is not the most important part of this residency,” Niizeki pointed out.

Niizeki met with classroom teachers midway through the 10 weeks to discuss what was working and what could be better. When a teacher suggested she use music to signal activity changes, Niizeki borrowed her teenage son’s harmonica. She stored it in a blue velvet sack safety-pinned to her tunic and noticed that children quieted down the moment she reached for it.

practicing sharing

Teachers liked in particular the chances children had to practice sharing in these classes. “I’m seeing a lot of collaboration and communication around sharing the tools,” said a teacher at the mid-way mark.

“Students have to learn to wait to use things.” The tools included two bright red pencil sharpeners with rotating arms, scissors, glue, and colored pencils.

Sharing is not easy. Dnaya and Kelvin—one from PS 281 and the other from PS 94— both adored the red pencil sharpener.

“I want it,” Dnaya said quietly, as Kelvin pulled it close to his chest.

As the weeks went by, it got easier to share. A teacher overheard a child say, “When you’re finished, can I use it?” Another heard a PS 94 child tell a River School child, “Thanks, Dude! I needed help with that!”

The River School kids were sometimes bothered by noises their PS 94 peers made, but Niizeki saw this as a natural part of the inclusion process. “They may be afraid of noises, but that’s honest feelings,” she said. “I don’t want to say, ‘Don’t be afraid.’” However, with exposure, she said, their feelings had the chance to change. Indeed, a River School teacher said that over time her students saw the PS 94 kids as equals.

The Inclusion Project has also fostered community among staff. Teachers who never spoke now greet one another by name in the hallways and bring their classes together for snack-time.

Parents reported other benefits: “My son is partially verbal,” wrote Carrie Isaacman in a letter to PS 94 Principal Ronnie Shuster. The art allowed him to “express how he sees things…through choice of color and design.”

Once the eyeholes were in place, Dnaya and Kelvin donned their masks and faced each other. Their conflict over the sharpener had been resolved, with a little help from Niizeki.

They laughed at their silly bag heads.

As Niizeki remarked, making a mask was not the most important part of this program. Mask- making was the shared purpose that led to better understanding, freer expression and budding friendships.

David Marquis couldn’t be more pleased. “Now there is a bridge,” he said. “A much better sense of community.”.•

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

A former teacher, Lydie Raschka writes about education in New York City