BY RICK RADER, MD * EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

After being on vacation for a week, Susan comes back all aglow. Aglow and exhausted. Susan is the Administrative Assistant at the Habilitation Center at Orange Grove and she was on a pilgrimage to Disneyworld with her family and granddaughter Presley. Aglow and exhausted best describes the human condition of spending a week at the Orlando mecca for what is billed (along with Disneyland) as the “happiest place on earth”. After all, what’s there not to love; it’s fantasyland personified, where everything is perfect, everything works right and the staff is falling over each other to insure you come back (and pass the strategically placed souvenir displays leading from everywhere to everyplace).

And of course not everything seems as it appears. Disneyworld may seem to be not only the best place to visit, but it seems like it must also be the best place to work. But like Hallmark Cards (where every staff member strides around coming up with expressions of love, congratulations and apologies for forgetting the adoption date of your mailman’s ferret) and Hershey’s chocolate factory (where workers can reach out and get a handful of Kisses right out of the vat) they are simply places to put in a day’s toil.

The Magic Kingdom, after all, is not only a corporation but a disciplined, formulated and regimented institution in a highly cutthroat competitive environment. While the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) is known to insiders as “The Company,” and the Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) is known as “The Bureau,” Disney is known to its employees as “The Franchise.”

The perceived bliss of working at Disney (visions of ink stained animators creating little creatures into humanlike characters and speaking in high pitched voices) came to an abrupt halt in 1941 when the Disney animators went on strike. Seems as if Uncle Walt instituted what they considered unfair “salary adjustments” to certain cartoonists and a strike was called by the Screen Cartoonists Guild. The strike occurred during the making of the animated feature Dumbo, and a number of strikers are caricatured in the feature as clowns who go to “hit the big boss for a raise.”

The animators at Disney weren’t the only pencil pushers who faced unfair working conditions in the industry. Cartoonists from Fleischer Studios (makers of Betty Boop), Pat Sullivan Studios (Felix the Cat), Leon Schlesinger Productions (Looney Tunes/Merrie Melodies) and a host of other animation houses went on strike, backed by their unions. After the strike at Disney, the morale at the studio went into a nose dive and over half of the 1200 employees were terminated. In a letter Disney reported, “We cleaned house at our studio and got rid of the chip-on-the-shoulder boys and the world-owes-me-a-living lads.” Before the strike the Disney ink squad felt as if they were one big happy family, but after the strike Walt felt betrayed and he was not sure whether he could trust anyone.

The world of drawing cartoons and creating embraceable cartoon characters is no different from any other creative craft. The creative types have to “sell” their ideas, their vision and their creations to the directors and the production staff. This cross current of “artistic creativity” and “the bean counters upstairs” is vigorously depicted in the automobile industry (“Let’s get rid of the key and install a start button.”), the pharmaceutical industry (“Okay, so we will have to downplay the four hour erection, but I think we’re onto something here.”) and the fast food industry (“It’s called a corn dog for now but we’re still open minded.”).

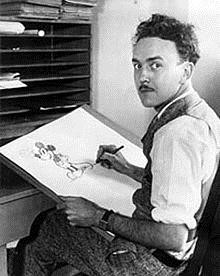

It was the dance between the animators and the creative directors that gave birth to the Theory of the Hairy Arm. No one particular animator is credited with being the first to dream up the technique. Some attribute it to Eb Iwerks, the co-creator of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit and Mickey Mouse.

Disney was a tough taskmaster who never complimented anyone in public but was quick to embarrass them in public and in front of their peers. Concept cartoons were submitted to Disney and he watched them in what the animators called the “Sweat Box,” a non-ventilated projection room. The animators would sit behind Walt and the directors of the picture, nervously waiting for Walt’s critique. Walt was very harsh and direct if he did not like what he saw.

Animators had strong allegiance to their design concepts and worked vigorously to perfect their characters before they would submit them for approval. These creative types would be devastated if their ideas or designs were rejected or ridiculed. As in the case of most creative artists they were thin skinned and took the rejection of their characters personally and felt they, not their “raccoons,” “mules,” “hamsters,” or “magpies” were being ridiculed and rejected.

Somewhere along the line one of the cartoonists submitted what he thought was a perfect little cartoon and drew the character with an abundance of hair on his arms. The director was incensed about the hairy arms and went on a tirade and used his pencil to mark “X’s” on both of the hairy arms. It worked. The hairy arms were a ploy, a distraction, a centerpiece for the director to focus on. While he rejected the “hairy arms,” he passed the other features of the character that the cartoonists felt were significant but risky.

Cartoons in the 1930’s and 1940’s had to look very slick; they hated anything that the cartoonists “added” to the character. What the cartoonists realized was if they added hair on the arms of each character, the art directors would be distracted from making other changes. It was years before the directors caught on to the canard. There are countless cartoon characters with features that would have been disallowed, discarded or nixed if it wasn’t for their initial depiction of having “hairy arms.”

The inclusion of “hairy arms” is a brilliant strategy that could be easily and effectively adopted by exceptional parents. Often, parents of children with special needs are denied requests at IEP (Individual Educational Program) meetings or ISP (Individual Support Program) meetings. The rejections are typically made by school authorities or provider agencies because of resources, manpower, accountability, culture or skills. Perhaps some of these programmatic components could be squeezed in by applying the “theory of the hairy arms.”

Parents of children with intellectual disabilities should try to include (virtually) unobtainable pie in the sky goals like, “Nathan will learn to pilot a single engine aircraft,” or “Gloria will spend the summer as a biker-girl with the Oakland chapter of Hell’s Angels.” While the school officials are scurrying around crafting a response that will reject the requests, they might not notice the accompanying proposals like, “will receive ongoing sessions of physical therapy,” “be supported in his desire to fly a radio controlled drone,” or “be able to be trained as a volunteer docent at the art museum.” Things that might be normally added to the list of, “let’s defer that until next year when the timing is more opportune.”

No telling what exceptional parents might achieve by putting a little more hair on those arms.